Interesteg

What makes it different from others?

Matialth

Good concept, poorly executed.

Fairaher

The film makes a home in your brain and the only cure is to see it again.

Francene Odetta

It's simply great fun, a winsome film and an occasionally over-the-top luxury fantasy that never flags.

tieman64

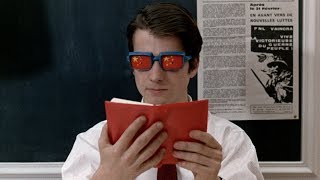

"Only the guy who isn't rowing has time to rock the boat." - Sartre Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote "Demons" in 1872, a novel about a group of young radicals in pre revolutionary Russia. Based loosely on Dostoevsky's tale, Jean-Luc Godard's "La Chinoise" watches as five young activists spend their summer vacation in a small apartment belonging to "wealthy factory owners who are out of town". Here they study Mao's "Little Red Book", a collection of writings on Chinese communism."La Chinoise's" first two act take place almost entirely within the group's apartment. Red, blues and whites – the colours of the French national flag – dominate. Stacks of Maoist literature line the walls and plastic toys litter the floors. A radio blasts Chinese news reports and occasionally silly Maoist pop songs. We're then introduced to Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Leaud), Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Yvonne, Henri and Kirlov, the only character named after a corresponding character in "Demons". It is implied that Veronique's relatives own the apartment. The kids are all in their late teens and early twenties, some prostitutes, others timid intellectuals, others related to bankers. "I'm ashamed of my wealth," Veronique says."La Chinoise's" aesthetic is now familiar, but back in the 1960s was deemed novel. Told in stylised bursts, this is a confusing amalgamation of agitprop, reality TV, documentary, cartoon, Brecht and conventional fiction. Like most of Godard's films, things only coalesce and take on power with repeated viewings. Godard hoped such a style would "shatter bourgeois aesthetics!", but of course the opposite proved true. Instead of a militant aesthetic (what he called "socialist theatre") which radicalised viewers and instigated change, audiences turned up their noses to what they deemed elitist and incomprehensible.Ironically, the film itself is about "clarity" and "gibberish". "We should replace vague ideas with clear images," one sign reads, whilst another kid states that it is "necessay to bring about the subjective and objective conditions that make revolution possible and render the use of force feasible". In short, they want to overthrow capitalism. The problem? How and what then? "There are different kinds of communism," one kid says, "different shades of red to choose from." Russian Communism, he then points out, does not truly incur the wrath of imperialist America. Chinese Communism, on the other hand, warrants the shelling of Southeast Asia and the escalation of fighting in Vietnam. Surely Maoism is thus "the right way"; a bigger threat to the status quo.This certainty is contested throughout the film. The kids are shown to be narrow-minded, sheltered, annoying, blind to ideological contradictions and nuances, uninterested in anything outside Mao and lost in their own private bubbles. They dream whilst the world spins, treating political ideology as just another pair of goofy consumer sunglasses to be picked up and discarded. On the flip side, these youths are sincere and Godard thoroughly sympathises and even agrees with them; after-all, history is littered with pampered folk like this getting the ball rolling on many human rights issues. Takes time, but still; you can't fight stupid.Godard title is a pun on the phrase "speaking Chinese" (speaking nonsense or gibberish), and also an allusion to "The Italians", a leftist cell beholden to the writings of Antonio Gramsci. Godard's cell, of course, is obsessed with Chinese rather than Italian Communism, they just struggle to morph theory into action. As the film progresses, they also become more militant. "We must suppress undesirable elements that compromise the whole," one morbidly states. Another makes a good point: "revolution costs money but the armies who put them down are free." Guillaume then learns the concept of "struggling on two fronts", which Godard turns into a specific metaphor: the revolution fights itself, its own failings and limitations, as much as the enemy.Veronique, the only character to come from wealth, eventually hatches a plan to both assassinate a visiting Soviet Minister and bomb a university. "Cut off one finger to save ten," her buddies nod like robots, and then: "We must participate in changing reality. Revolutions require terror!". In the film's best scene, Veronique discusses her plans with Francis Jeanson, a real life philosopher who was once arrested for supporting Algerian independence movements (Algeria was once a colony ruled by the French Empire). Jeanson sympathetically stresses nonviolence, seeks to talk Veronique out of her blood-lust, but she doesn't listen. If you're looking to change the rules, why start by abiding by them? Godard's shot composition is ominous: Veronique's hurtling toward history, a history to which Jeanson's back is firmly turned to.The film ends with Veronique's terrorist attacks comically failing. The group then disbands, one member committing suicide, another quitting his job, another emigrating. "Sound and fury scare me," he admits, gobbling down food in a parody of consumerism run amok. As for Guillaume, he's enveloped back into the folds of capitalism, selling fruit and metaphorically assaulted by rotten vegetables. Occasionally he visits the "Year Zero Theatre", in which he symbolically chooses who to free: a plump woman, or a skinny girl, both knocking on an invisible door. Year Zero, of course, alludes to the group's longed for day of victory. "All roads lead to Peking", a sign says, but it's a long walk. "I thought I made a leap forward," Veronique admits, "but it was but a small, timid step on a long march." The group's apartment is then sealed shut, and with it a zeitgeist, Veronique's relatives excavating rooms and unceremoniously dumping Mao's red books. Silly girl, they think. Then came 1968, in which the May day strikes (the Tet Offensive occurred weeks earlier) promptly made a fortune-teller of Godard. Here, over 11 million French workers/students took to the streets, 22 percent of the country striking. France's economy crawled to a halt. This little mini-revolution ended two weeks later, partially betrayed, no less, by the French Communist Party. Henceforth Europe's left-wing became increasingly right. Godard would slip into depression.8.5/10 – See Fassbinder's "Third Generation".

Emil Bakkum

I like the films of Jean-Luc Godard, because they are so intimately intertwined with this rebellious and bizarre episode of my youth. Rebellion has infested my brain, and by now this bacteria has completely taken over command. As such, of all his films La Chinoise has perhaps made the deepest impression on me. It is amazing, it opens unsuspected horizons for you. Godard is a child of his time, and loves to break established Rules and do what God forbids. Hence the label Nouvelle Vague (don't call it New Wave!). At the same time the piece is hopelessly outdated. True, Mao had original theoretical concepts about politics, and it is not surprising that his little Red Book became popular, especially among students. After all, the church was in decline and no longer able to guarantee the flow between the lower and higher strata, thus creating room for new ideologies. Unfortunately Mao and his bunch made an attempt to realize their heaven on earth. They called it the Cultural Revolution. At the time, the Dutch-French film-maker Joris Ivens produced some impressive propaganda films about it. Especially the French, since 1789, love anything that vaguely looks like a revolution. The REAL result for the Chinese people can be seen for instance in the recent Chinese film To Live. It is ugly. Here in Europe things went better. The ideas of the Cultural Revolution inspired some European intellectuals with Maoist sympathies to give up the university, and mingle with the common workers. Others formed collectives, who supplied cheap medical and judicial services to the people. Actually not such a bad thing, as long as you could stand their ideological humbug. However, if you use the Red Book as a new bible, and apply the ideas without any knowledge of men, of course you may end with bizarre conclusions. This is what happens here. This is what Godard, freed of proved and professional wisdom, throws on the screen. This is Godard at his best. Godard uses techniques like the interview, the monologue, the flash, which to an amateur may look, ahem, amateurish. Five young adults learn the Rules in the Red Book, but don't actually understand them. Just like other sects, the predictable result is extremism and self-destruction. Godard does not portray Maoism, but ideological fanaticism in general. This is heavy stuff. Luckily, Godard the liberator saves us, with the Nouvelle Vague brilliantly keeping aloof (is this English?). The trick of Godard is the play of the youngsters. For instance when they entertain themselves with toy guns or toy fighter jets. Or when they paint slogans on the walls. When they do exercises on the balcony. When a girl and a boy sit like a languid couple, and suddenly the girl breaks up their relation (boy, dumbfounded: Why do you say this? Girl: You'll understand). When a member is expelled from the sect, and wonders: shall I take a job, or else migrate to Bolshevist Germany? Questions of life, presented in blank naiveté. The music supports the absurdity of the situations. It is almost a symphony, with the phrases of Mao as the delightful songs. In short, it is amazing, rewarding. Having written this, unfortunately not every potential materializes. Does Godard really liberate us, so that we can retire in heaven, with private swimming pools around each corner? Will access to the Hall of Eternal Glory be granted? I fear that somewhere between the screen and the hall, this produce will find an inglorious ending in a drawer of the archives.

bobsgrock

This is more of a history and social lesson than a film and perhaps that is what Godard intended. There is no real plot or narrative to speak of, but rather various scenes showing a group of French students in their lair of socialism and Communism as they discuss and digest the many teachings and ideas from Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Marx. One thing I still don't understand about Godard is if he is advocating these beliefs or against them. Still, the film is very well-made with the primary actors giving very believable performances and Godard still messing with the basic fundamentals of film making. There is one great scene that is an unbroken shot of what must be at least 7 or 8 minutes in length. It takes place on a train passing through Paris and shows Anne Wiazmesky talking to a French politician about the cons and pros of revolution and violence. It is interesting to listen to as well as watch. This film is the same way and so is this director, though certainly not for everyone.

jameswtravers

La Chinoise, possibly Godard's most political work, is very much a film of its time. The mid-1960s was a period of great social change and political tension. America was at war with Vietnam, relations between Russia and the West were growing ever cooler, and the Far East was awakening to the hymn of the Chinese cultural revolution. Nearer to home, there was increasing tension between the French government, public-sector workers and the student population, which would come to a head in the following year with the student riots. It would have been more surprising if a French film director had not created a film like La Chinoise.Here, Godard's method of film-making is at its most primitive and extreme. In a sense, it is hardly a film at all, but a series of sketches nailed crudely together, interspersed with some pretty wild pop-art like imagery. The end result is raggedy, colourful, a bit rough round the edges, but also quite witty.It is not clear from this film where Godard's political allegiances lie. We can see that he is against the hypocrisy of the Amercain interventionalist policy, which he suggests are derived from imperialistic motives. However, it is less certain where he stands with regard to the Maoist communist ideal. The discussion between the students appears incredibly naïve, didactic, to the point of self-mockery. And the fact that the students are evidently from a middle class background seems to further underline the contradiction between their personal circumstances and their apparently deeply held beliefs.It is probably safest to regard La Chinoise as Godard's view of how students consider the politics of the time rather than as a portrayal of his own political views. With that in mind, the film reads as a very perceptive study of the naivety of young adults. For these people, freed from the need to work for a living as they pursue their studies in comfortable surroundings, it is easy to contrive a woolly-minded simplistic picture of the world, and to believe that a few bombs in a few school classrooms will solve everything. As the film reveals in its final segment, the dream ends as soon as the degree course has ended. Godard seems consciously to be admitting that his film will change nothing but that it is nonetheless valuable to at least make his statement.